What You Can’t Read Behind Bars in New York

I did not expect a book to vanish at the prison gate.

Out there, books are everywhere. They are stacked on shelves, glowing on screens, sitting in coffee shops, waiting at libraries. However, in here, they arrive like visitors. Each one passes through mailrooms, officers’ hands, and review committees before it can reach mine. Some make it. Others are stopped, returned, or redacted before I ever turn a page.

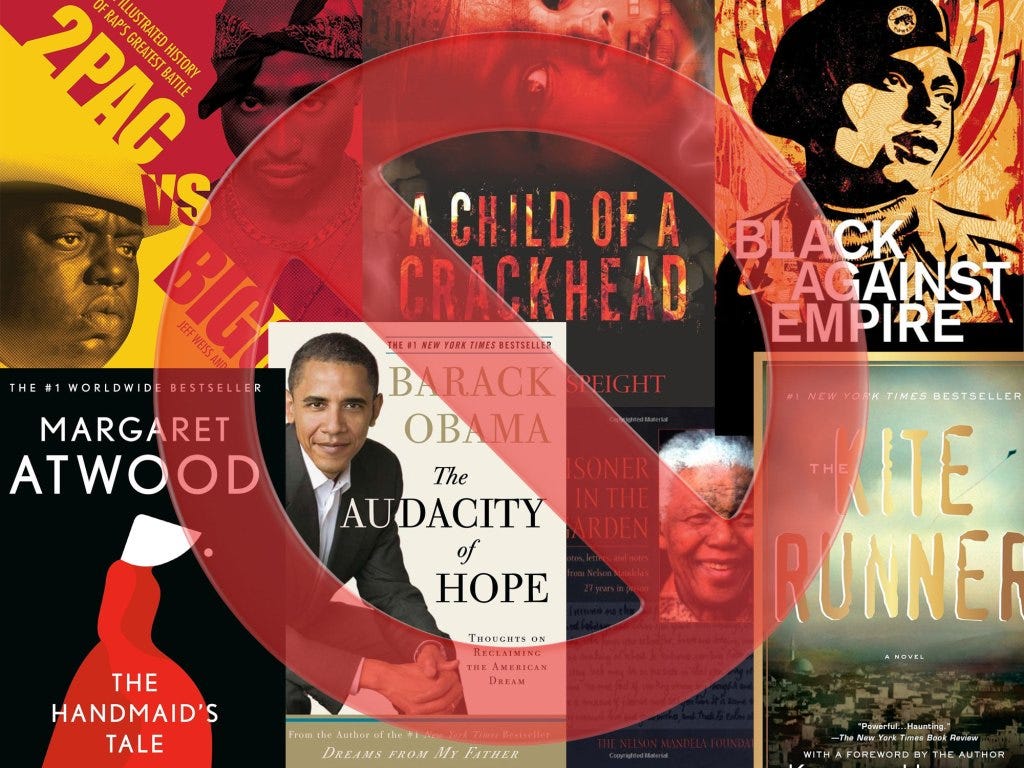

Last year, someone at Ulster Correctional asked for Native Son. Richard Wright’s classic, taught in high schools, dissected in college classrooms, never made it past the review. Officials alleged it might “incite violence based on race.” A novel written in 1940, still speaking to the wounds of segregation and racism, judged too dangerous for the men who live the sharp edge of those wounds today.

This is not an exception. It’s routine. Books disappear because of what they contain, or what someone believes they might contain. A novel, a history of Attica, a manual on web design, even a Colorado vacation guide, all treated as potential threats. Sometimes pages are sliced out, sometimes entire volumes are barred. At Eastern, In Cold Blood was stopped. At Elmira, even the Alcoholics Anonymous “Big Book” was turned away.

When a title is blocked, the reasons are written in vague phrases—“threat to security,” “encourages disruption,” “depicts violence.” They tell you little, and they don’t have to tell you more. Behind the words sits a committee, maybe three or four staff, sometimes just one, deciding what I can and cannot read. One book is denied here, admitted there, approved one month, banned the next. There is no consistency. Only power deciding who deserves access to knowledge.

Books are more than paper in prison. They are escape. They are education. They are mirrors, showing us who we are, and windows, letting us see beyond walls that close tighter each year. To deny a book is to deny possibility. It is to close off a door that, for many, may be the only one left open.

The justifications sound familiar. Safety. Order. Security. As if barbed wire, locked doors, and armed officers are not enough. As if a paperback poses more danger than the weight of confinement itself. What is really at stake is control. Control over what we can learn, what we can question, what we can imagine.

Kevin Mays, who spent nearly three decades in New York prisons, once said: “During the course of slavery, the worst thing you could do was get caught reading a book. Educating yourself is about self-determination, and they didn’t want that.” He is right. Denying access to books is not just about preventing disruption inside. It is about keeping people from building the kind of knowledge that could outlast these walls.

When a book is blocked, it does not vanish only from one man’s hands. It vanishes from the shared conversations of dorms and cells, from the letters home that carry reflections, from the way men teach each other to read and write, to think and debate. It is a quiet erasure, invisible to the public, but felt deeply in here.

Most people outside have never thought about banned books in prisons. They hear about book bans in schools, they see the debates at school boards and libraries. They rarely see what happens behind these walls. But in here, censorship is sharper, more absolute, and often more absurd. It reaches into the very spaces where words mean survival.

I cannot stop the mailroom from rejecting a book. I cannot stop the committee from cutting out pages. But I can speak about it. I can say that behind these walls, censorship is alive and well. And I can remind whoever reads this that when a book is silenced in prison, it is not just a book that is lost; it is a life line, cut short at the gate.

You should send this to PEN's Prison writing contest. They have been fighting to get books back on the approved reading list

Thank you so much for writing this wonderful article! In my experience at Books Beyond Bars, we thankfully don’t get book rejections very frequently compared to other states. What I do wonder is whether the facility always tells us when a book is not sent to the recipient. We have sometimes received blank rejection letters that do not tell us which book was rejected or even who it was sent to. Of course they never respond to inquiries for further clarification.